Ann Leda Shapiro

in conversation with Gan Uyeda

on her solo exhibition Light Within Darkness

January 30, 2024

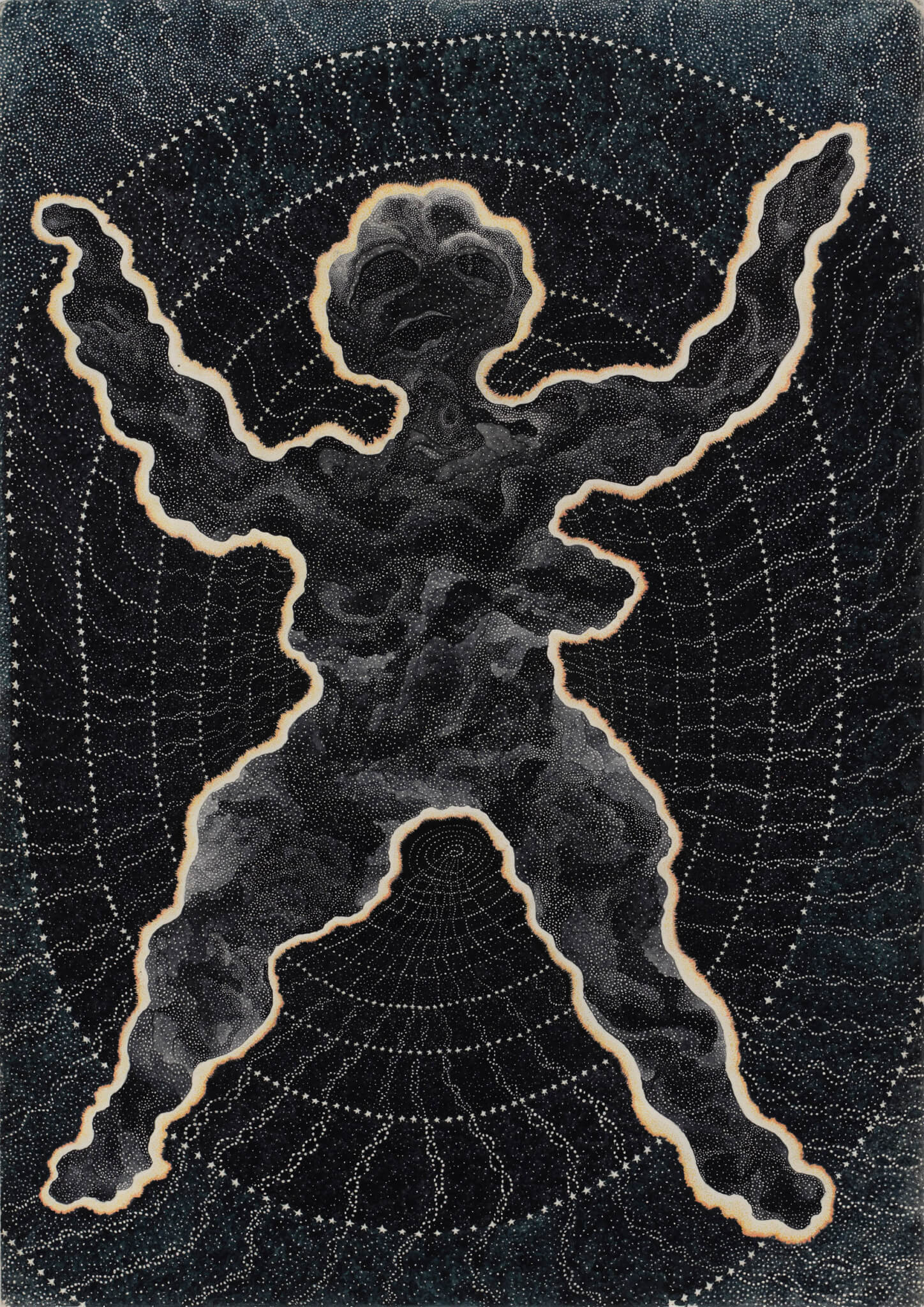

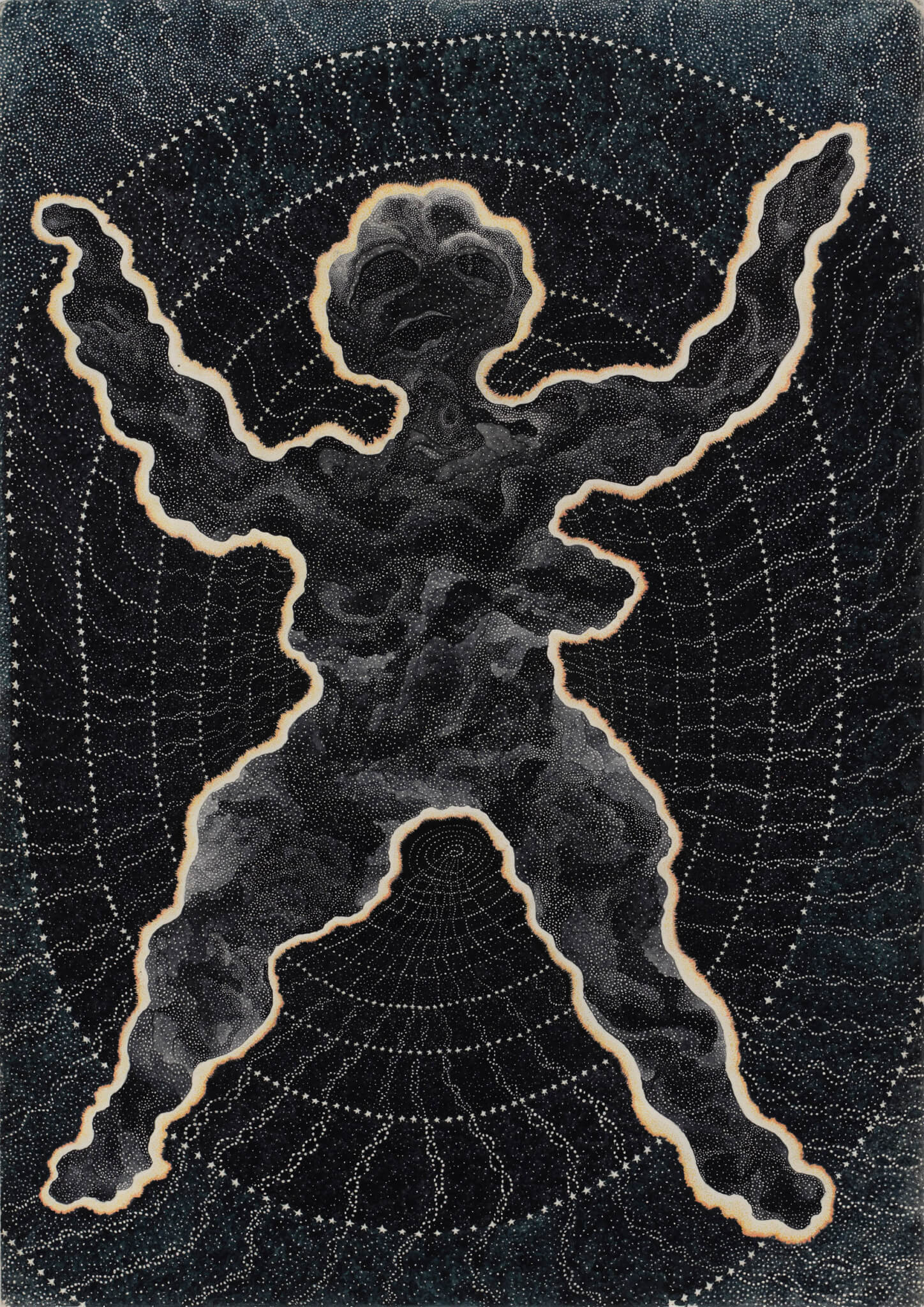

Ann Leda Shapiro, Out of the Web, 1976. Watercolor on paper, 20 x 14 inches (51 x 36 cm.)

Ann Leda Shapiro was born in 1946 in New York City. She was the subject of a solo exhibition at the Whitney Museum of American Art in 1973, an exhibition that was censored during its run for imagery that challenged norms around the depiction of nonbinary and gender non-conforming bodies. After living and teaching around the US and the world, in the early 90s she settled on Vashon Island, a ferry ride from Seattle where she has maintained an acupuncture practice and an art studio in a converted canoe storage. Throughout her life, her paintings have vividly recorded her outlook on the intertwining of life, death, embodiment, and landscape. On occasion of her exhibition Light Within Darkness at François Ghebaly Los Angeles, Shaprio spoke with gallery partner Gan Uyeda about her background and influences, the development of her visual vocabulary, and what it means to look back at four decades of painting.

Gan Uyeda: Let's start with "Out of the Web" from 1976. Can you take us back to that time and your state of mind while creating it?

Ann Leda Shapiro: "Out of the Web" was born during a time when I was beginning to engage with feminism. It is a reflection of breaking forth and emerging. My technique is deeply meditative and has been influenced by my appreciation of Buddhism. I can’t say I’m a “Buddhist,” but the tiny repetitive patterns of painting around white emptiness provides some inner peace. I have always loved Middle Eastern prayer paintings first viewed at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, embodying themes of light within darkness.

Uyeda: Looking at this piece now, do you think it anticipates a lot of your future work? How do you perceive it now?

Shapiro: It is a pivotal piece. It’s part of the transition where I started to blend the body with its surroundings, questioning and exploring the lines that separate the two. It’s where I started to bring the emotions within the body and within the landscape together.

This theme is something I come back to throughout my work. I pursued it in studying chemistry and biochemistry, Chinese medicine and acupuncture. I wanted to understand more deeply what is aliveness and what is death.

Uyeda: "Falling" from 1980 captures a kind of scientific vision. It feels cellular and elemental. Could you share the ideas behind this work?

Shapiro: "Falling" is an exploration of motion within stillness, which is a constant throughout my work. All the principles I use in my healing practice are reflected in my painting. When I am practicing craniosacral work, when I focus on the fascia layers within bodies, there is unwinding that occurs—a stillness within motion and motion within stillness.

Uyeda: Can you talk about the transition into acupuncture and how it has influenced your art?

Shapiro: After I graduated from UC Davis in the early ‘70s, I taught at various universities for about 14 years. I referred to myself as an academic vagabond because in those days it was difficult for women to get tenure track jobs. The last place I taught before moving to Vashon Island was at UT Austin, Texas. A dear friend of mine was dying of AIDS so after class I volunteered at an AIDS clinic where I was introduced to Chinese medicine and it was like a light bulb turned on.

For me, it was about fundamental questions that I had been asking in my life and my art. What is aliveness? What is death? How is microcosm seen in macrocosm and vice versa? How are we all interconnected? I thought about continuums and how the yin and yang relate not in opposition but in complementarity. That’s how I got into Chinese medicine. I thought I’d go back to teaching; I had no idea that I would fall in love. And I did.

Uyeda: How has acupuncture and healing as a practice impacted your painting?

AShapiro: These two practices are one and the same. Sometimes when I’m working with people, I see pictures. It goes back and forth, the Chinese medicine, the cranial work, the unorthodox ways that I help people; these all feed into how I represent different forces within my painting. I almost have a sense of X-ray vision, like seeing through and into people. In my painting I take the body apart and put it back together again, using what was in the interior on the exterior. My palette, for example, often comes from looking through microscopes and the colors of histological stains.

The idea of qi is an important concept in Chinese medicine and it plays out in my work too. The translation of qi is “matter on the verge of becoming.” It’s that moment when we are living and dying simultaneously. And that, in a sense, is what I’m trying to paint.

Uyeda: How do you think about physical and emotional vulnerability in your work?

Shapiro: I’m working with that idea continuously—vulnerability. It’s a challenge, how to portray the quality of vulnerability. In some ways I want to do the opposite of what’s popular in all the museums and galleries and what I see online; I want to do little things. That’s the first word that comes to mind, little, but that’s not the right word. I want to do intimate paintings, slow art, vulnerable art, I want to do the opposite of big and brash. I think we’re all painting about our lives. So whether to call it identity or autobiography, I don’t know, but when I paint something, even if it’s a tree, it’s about me and the stories from my life.

Uyeda: The question of identity and representation brings up what happened with your show at the Whitney Museum in 1973, and the censorship of paintings that depicted non-normatively gendered figures. Reflecting on the censorship at the Whitney Museum, how did that experience impact you?

Shapiro: I was shocked. I had no idea I was doing anything that was particularly controversial. It was really difficult. At that time I was living in the Bay Area and I hadn’t moved back to New York. It made me commit to not censoring myself. I withdrew from the art world. I only showed at university galleries or alternative spaces. I never even attempted to show with galleries. I felt so outside of the art world for many years. It wasn’t until forty years later when I applied for a Creative Capital Grant and Catharina Manchanda was one of the readers for the grant—she’s the contemporary curator at the Seattle Art Museum. I didn’t get the grant, but she called me up and said “Who are you? Can I come visit?”

Her visit eventually led to the Seattle Art Museum acquiring my work in a roundabout way. The artists Matthew Offenbacher and Jennifer Nemhauser received a grant that they used to buy art by women, people of color, and gay people to donate to the SAM as their collection was deficient. So two of the formerly censored paintings from the show at the Whitney are now in the permanent collection at the Seattle Art Museum. From then, in 2015, things started changing and more people became aware of my art.

Uyeda: How do you think about the representation of gender in your work?

Shapiro: Many of my figures are blended bodies. I think about the fetus, the male and the female all merged in one body. That’s how I feel about life. I feel like we are all everything.

It’s changed over time. Back in the ‘70s I was asking the questions, “What is male? What is female?” Because that was the beginning of feminism. I was thinking about aggressiveness and non-aggressiveness. In graduate school, the panel of male professors—I called them the Seven Mustached Men—I liked them individually but together they were a pack. “Are you purposely trying to be a primitive,” they asked me during my first review and I cried. Their questions didn’t make sense to me.

Growing up, my parents were communists and I was called a red diaper baby. They eventually left the party but when I was in high school, my Friday night dates were going to New York School for Marxist Studies. So that’s a really important philosophy for me. Because of this upbringing, I would look at questions of gender more from a culturally, economically, and materially rooted perspective. And so in the 80’s when I got involved with the Guerilla Girls, that was so fantastic. “The Conscience Of The Art World.” We could do statistics and look at the numbers, the economics, and we could see the data that underscored what we were saying about the imbalances in the institutions of the art system. It was a lot of work, but it was life changing.

Uyeda: In your work you create many parallels between bodies and landscapes. Could you share the significance of these rhythms?

Shapiro: A windy tree in my work, that’s a self portrait. It’s a way to make sense of the world and to make sense of myself in the world. When I make a painting I’m working with three of four ideas at once. You could call it a visual pun or entendre. There may be a cellular form that is also a coffin and also a histological chart and is also an atmospheric phenomenon. Bodies are enveloped by softness and hardness, and sometimes I depict both at the same time like when my clouds are like stones and stones are like clouds. My figures are observational on the one hand, like when I’m looking at my patients or seeing larger forces within society. And on the other hand they are psychological of myself and diaristic of things that happen to me and struggles that I’ve faced internally.

The parallels of the body and landscape bring up a sense of kinship and company. When I was growing up, the Museum of Natural History in New York City was very impactful for me. I learned to draw there by sitting and looking and feeling and drawing. I felt a sense of company with the objects and dioramas and animals. It was like traveling around the world. It was so incredible. I wanted to put my hands around the whole museum with a big, giant hug. The seeds of how I lived out my whole life, those seeds were all there.

Ann Leda Shapiro’s Light Within Darkness opens at François Ghebaly Los Angeles on February 22, 2024 and includes works from four decades of paintings. This interview was conducted on January 30, 2024 and has been condensed and edited for clarity.