Noel McKenna

in conversation with Wes Hardin on his solo exhibition Thoughts Covered in Moss

October 3, 2023

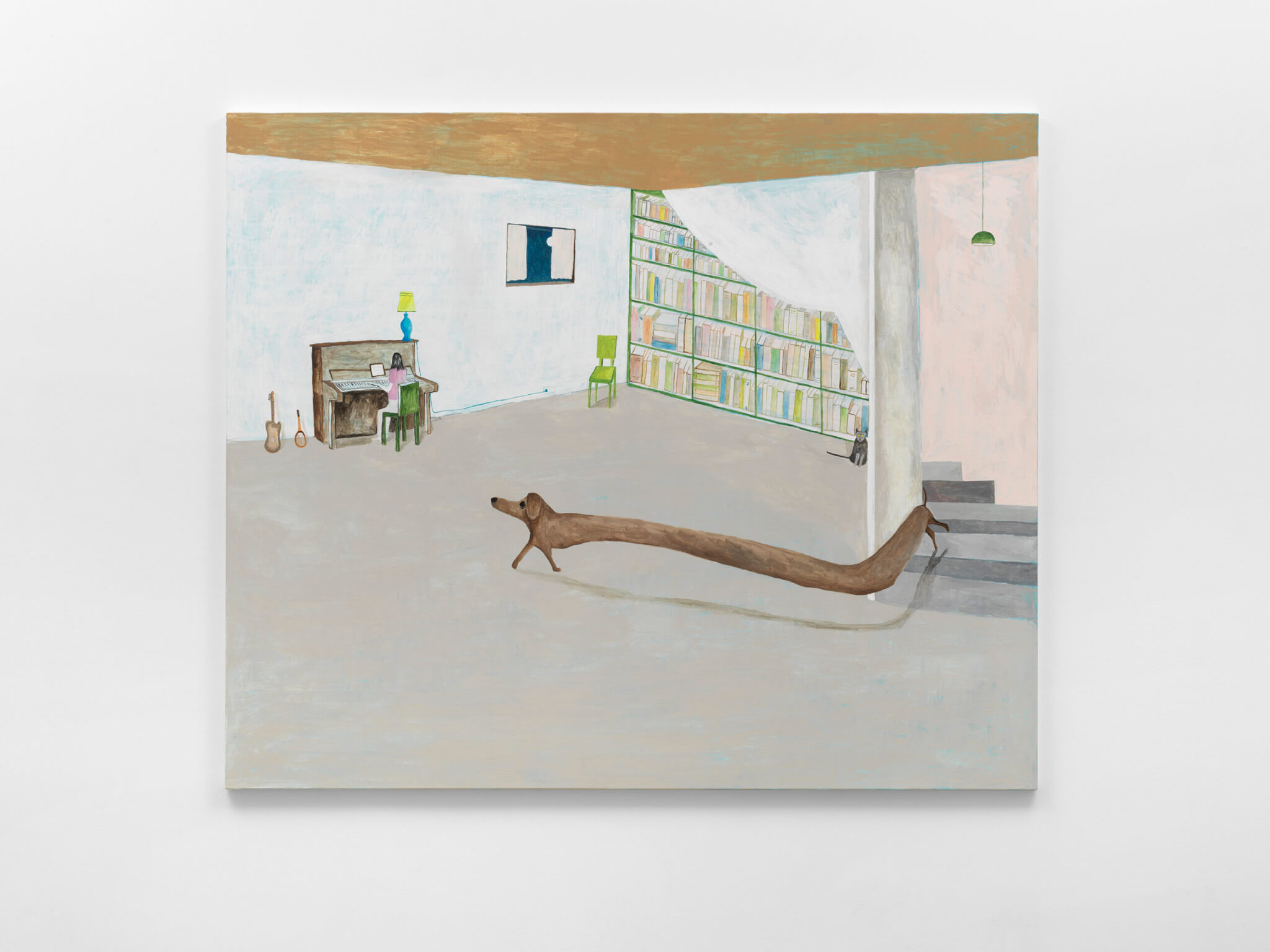

Noel McKenna, Thoughts Covered in Moss ..... H, 2023. Oil and acrylic on canvas, 59 x 71 inches (150 x 180 cm.)

Wes Hardin: So first things first, I want to say thank you very much for sitting down with me to chat. It’s pretty safe to say that in the world of contemporary Australian art, you’re a bit of an icon. You’ve shown across the continent and in virtually every major museum. For some decades now, you've been crafting really quite iconic, recognizable images of domestic interiors, the Australian landscape, personal memories––oftentimes within an almost diaristic sense, and always from a place of personal observation. In this exhibition, Thoughts Covered in Moss, I think we encounter a very quintessential subset of that observation, which is the home, among others. And so in that vein, I was wondering if maybe we could start off with just a bit about the development of what I think, and I think most people would agree is a very recognizable personal style?

Noel McKenna: Well, I think it's best to go back a few years, I suppose to when I first started painting and at school. There was never any sort of art education in the primary schools that I went to. I ended up enrolling in architecture in Sydney straight out of school, and it was very casual. The first year there were no exams, we’d just have a live model and so that was the first time that I'd ever really done drawing. I was probably 17 or 18, I got through the first year and had a few problems. Back then, the rendering of buildings and plans was very important. As an architect, you had to be able to present your ideas in a clean, precise way. There was a particular method for drafting, with very fine graphs on tracing paper. You had to use slide rules and everything, and I was never able to really do that. My drawings were always quite messy. And as a result, one of the lecturers took me to his office and said that the staff here, we've sort of decided that you will have difficulty graduating in architecture because of the quality of your drawings.

WH: You were quietly given the boot?

NM: Sort of, yeah. I didn't entirely fit in with the rest of my class and the lecturers, so they suggested that I go to art school. They said, “oh look, your drawings are so messy. They might like it there.” I didn't really know whether to take it entirely seriously, but during the start of my second year is when I gave it a hard think. I was living at home with my parents at the time, and I used to just do little ink drawings of horses on the kitchen table. And I thought, well, may as well apply. So I did. And it wasn't actually easy for me to get into art school either, because you have to do an interview, which I didn't know. And I brought along these tiny little drawings and they said, “oh, they're a bit weak. Have you ever done a canvas?” I said I don't know what canvas is. They eventually took me in and I enjoyed the three years at art school. So that was kind of an unusual start to becoming an artist.

WH: Yeah, I mean, I think a few decades later it's that general complaint from the architecture discipline that’s a pretty important piece of this style equation for you––a mismatch in vanishing points, a flattening of space, the elongation of figures that's incredibly idiosyncratic. You're definitely not getting that from AutoCAD.

NM: Yeah, I eventually married Margaret who was an architect, and so I got to know quite a few architects in Sydney. Many mentioned that they actually missed drawing, so they’re encouraging students to draw again.

And going back to the idea of style, when I first went to art school I didn't even know what acrylic paint was or anything. So there were lots of different styles that I cycled through. I did large-scale abstract expressionist things at one point, which didn’t really work for me. I think when I was at school, I probably never did anything that you would say looks like what I do now. Eventually, I went down in scale a bit and just started doing drawings about my everyday life, I suppose. I used to take a lot of photographs in those days, black and white photographs. I'd often take pictures of the suburb where I lived. I photographed my dogs. So that’s where it all sort of really started. I suppose the germ of my current practice, just painting my everyday life.

WH: Pivoting slightly, and this sort of ties into the next question, I look at your exhibition history over the last couple of decades and in every exhibition, this one included, I see a work that's referential to travel. In this show, we have Norway (2023). A little while back I saw a small artwork, Finland (2015). We’ve talked about this before, this is your first bonafide solo exhibition in New York. I think among most Australians, you've probably spent quite a lot longer in the States than maybe the average. New York has been this recurring travel destination as well as an artistic subject for you––now I’m thinking of a few really remarkable paintings of yours from the 1980s of Williamsburg and downtown Manhattan. Could you tell me a bit about your travels, and of course your relationship with the city?

NM: Yeah, I certainly like to travel, and it’s an excellent time to paint. Before I married Margaret, I'd never actually traveled at all. We went on a honeymoon after marrying in 1986. Landed in LA, stayed there maybe a week and then went to New York. I had an American friend whom I met at art school in Sydney. She was living in Williamsburg, so we stayed with her for a while. It was a much different area then than it is now. After about a month in Europe we came back and stayed in Williamsburg again. That was where I first fell in love with New York, I suppose. Just everything about it. There's always so many interesting things to see, and the museums and good galleries. We’ve come back maybe 10, 11 times since. Always in November or December because I quite like winter in New York.

WH: With your exhibition here now in full swing, I was hoping to turn to an abbreviated walkthrough of some of the artworks in the show. In Thoughts Covered in Moss, as in your practice at large, I think the viewer takes away a really palpable sense of play from many of the works, in terms of things like form, styling, space and composition, and scale especially. As a jumping-off point, I think it might be interesting to begin with one of the smallest works in the show, the aforementioned Norway (2023), an interior scene and a really concise example of your sensibility toward things like color and organization—the bike in the corner, the window, a beautiful sort of terre-verte green, and of course the little mouse hiding behind the leg of the table. How did some of these ideas originate?

NM: I think it’s generally best to start by speaking about how I feel about the interior. The interior is maybe the dominant thing that I’ve explored in my work for the last 15 years. I’ve a definite feeling that the interior is so important because of how much time we spend there, not only in the home but also the workspace, or a museum. I see the interior as a place of shelter in some ways. You shelter from the weather, or you come home if you've had a hard day and the interior is somewhere where you can relax and gather your thoughts. The mind in some ways is an interior also, where you concentrate on things that are important to you.

So it's a symbolic thing that I revisit often. In Norway (2023), the bicycle in the back sort of represents me, because the bicycle is very important in my life. I don't drive. I ride it everywhere. I use it for exercise, and I've got a good racing bike. I love watching the Tour [de France]. And that the little mouse has to do with a residency I did at Robert Wilson Watermill on Long Island in 2016. Tori Rains was an artist there at the same time. We lived in an offsite campus together with a few other artists, and we got to be quite good friends. One morning she was out taking a swim and found a dead mouse in the pool, so she took it out and buried it on the site. Ever since then I've sort of seen her as the mouse.

WH: Then at the opposite end of the spectrum in terms of scale is Thoughts covered in moss ….. H (2023), which is the largest work in the show. It’s the title piece, and also sits at the focal center in the gallery space. Could you tell me a bit about the origin of the title, or at least your general approach?

NM: Yeah. Well, I think if I had done that painting three years ago, I may have just called it “Hound Coming Downstairs.” But I've got good friends in New Zealand who are poets, and I often stay with them. I think in July of last year I went there for maybe the first time in three years. The first day there I got Covid, and in New Zealand there wasn't a strict isolation policy anymore but you were advised to stay at home. So I spent two weeks at their house with little to do. They’ve got a great collection of poetry books and art books and everything. In the room I was staying in, there were some books on Dada poets, and I particularly liked the poet Tristan Tzara. I think he was Romanian, he changed his name. But he was one of the original Dada poets in Switzerland. He started Cabaret Voltaire. He talked about how he used to get a newspaper, tear out words, just random words, put them in a bag, pull out a word, and that would sort of start him off on a method of arranging words. And while I didn't actually do that for my titles, whenever I do a painting I write down words that come to mind from looking at the image and then I arrange them in a way that I find interesting, or that I think suits the image. My friend has a daughter who plays the piano and her name is Harriet, hence the “H.” I put that personal connection in partly because the space shown in the painting is somewhere I’ve actually been before. Of course, as you mentioned the perspective is all wrong, and I've probably moved a window somewhere. So it’s more like a memory of space.

WH: Before we start talking about the central figure –

NM: The dachshund.

WH: The dachshund, yes. I actually wanted to, in relation to that, bring up something that we've talked a little bit about before, which is your process. You often begin paintings without a particular organization in mind, instead starting from individual pieces or elements and constructing the works almost piecemeal. Your ideas on the canvas are, more often than not, worked through and organized in real time, as opposed to a vision that you're workshopping via, say, lots of preliminary sketches. You're not approaching composition like a muralist, you're approaching it like Tzara.

NM: Yeah, I like to come in, not entirely blind, but from a place of openness. I don’t think I’ve ever done a preliminary sketch. I do a lot of ceramics, little tiles, and occasionally I'll do a tile and I’ll actually blow that image up into a painting. For Thoughts covered in moss ….. H (2023), the only thing I seriously had in mind beforehand was the spiral staircase coming down. It sort of dominates the space in the house. And, of course, there are certain technical things with depicting a spiral staircase. It seems simple, but in order to make it appear real, not realistic, but real, there are a few issues. In that painting, once I got the spiral staircase the rest basically just came from that. The dog was always going to be in the painting, but I wasn't necessarily planning on such an exaggerated form. I started with the regular dachshund shape coming down the staircase first. But there’s this big, expansive space from the staircase to the piano, which didn't quite work. So the dog sort of got longer and longer…

WH: Could you tell me a little more about the dog?

NM: The dog I've only actually met once, and the woman’s got two of them. But look, there are so many gray dachshunds where we live here in Sydney, you kind of just know them. And when I was growing up in Brisbane, one of the first dogs I got to know was a dachshund that lived on our street. So I've always had an attachment to them. They’ve just always seemed to me a really smart dog and just lots of character, which I like about them. Their spirit is not necessarily in keeping with their size. They're a very strong dog, which you don't, just by looking at them, you don't get that. But when you get to know them, they're quite a strong-willed dog.

WH: We’ve talked before about how their reputation among Americans especially is at odds with their original vocation.

NM: They were bred to hunt.

It's like poodles. Poodles are a hunting dog too. Good water dogs. And the haircut they have is for when they go in the water. When they get out, the water comes down and just drips off so they can dry a lot quicker. People don’t realize that it's a practical thing with the poodle. And it’s a similar story. I don't think many people use poodles as hunting dogs anymore, but they're a good water dog. They used to go out, get the duck, whatever, and bring it back in.

WH: Now I'm thinking of a really fabulous poodle painting that you made earlier this year. I'm trying to remember which exhibition it was for.

NM: I've done a few, could have been one. I had one at Art Basel this year, which was a gray poodle in the middle of a room. I think it was called Reading Room (2023). It was like a library behind the dog.

WH: Yes! Reading Room (2023). That one was great.

NM: Yeah, I keep a big stockpile of photographs, and I've got lots of photographs of rooms with books, fireplaces and whatnot. That work comes from the nice reading rooms you see when you go to some big libraries. Just comes about from things I've seen.

WH: There’s another really dynamic work in the show called Mother's Eyes (2023). Just in terms of color, we get a really beautiful interplay between green and this delicate, light ruddy pink. I think of Milton Avery among others. And then of course there’s the Félix Gonzáles-Torres cameo, Untitled (Perfect Lovers) (1987-1990), and the doubling of figures throughout the work. Could you tell me a bit more about the ideas at play here?

NM: Well, it's interesting you mentioned Avery, because Avery's an artist I’ve always liked. I’ve actually loved so many American artists over the years, going back to when I first went to New York. Joseph Cornell, Arthur Dove, William Eggleston has been a big influence on me with his photography, the way he photographs the everyday. Louise Bourgeois, Lee Friedlander, Phillip Guston–

WH: I definitely see Guston.

NM: To have the chance to see a lot of these artist’s works in the flesh was very important for me when I would visit. And that painting, Mother’s Eyes (2023), it’s an interesting thing how it came, because it did really just start from the two clocks. I’ve used clocks in my interiors a lot because I suppose time, well, it’s an important symbol to all of us. We have a limited amount of time here. The clock's ticking all the time, as they say.

So that's one of the reasons why I put the clock in. And it was a conscious thing to then place items in pairs. When you put two objects beside each other, the negative space that’s between them is very important I think. In the painting, you think about the cats, you've got one cat standing, one sitting, they're both facing each other. It appears simple. But, say I’d made the head of the cat that’s sitting a little higher and closed the space a bit, I don’t think it would have been as interesting a composition. So in all my works, negative space is very important, the space between things. And then you go behind the cats, you've got the two wine bottles, you've got the two shoes in front of the bed, which more or less are my shoes. And on the bookcase there's two objects. You've got the truck and the cup, the curtains, there's two curtains. It's one of my favorite works in the show because of that.

WH: I totally agree. And I actually have a question that I’ve been meaning to ask you about Mother’s Eyes (2023). One of the more popular contemporary readings of González-Torres’s Untitled (Perfect Lovers) (1987-1990) is as a piece about death and anxiety, a kind of memento mori–

NM: It was done as a commentary or an homage to his partner who died young of AIDS, I think.

WH: Exactly, and we as the viewers are queued into this kind of dramatic irony, which is that inevitably, whether because of shoddy industrial quality control, or designed obsolescence, what have you, that the two will fall out of sync in keeping time, or the cheap AA batteries in one clock will give out before the other, and at some point it'll just be a single clock that's ticking, or neither. And so I’m curious as to your thoughts on this in relation to the painting.

NM: Yeah, I think I'm not a hundred percent, but I think they have, they're able to, when the battery does die, they're able to put a new battery in. Not a hundred percent, but––

WH: [Laughs] I think they do. I think they do. I think it's just the knowledge, right? Or the position that the viewer is placed in?

NM: And it's obviously not an expensive clock, is it? It's just a cheap thing. But I suppose, well, that is something. It's sort of the everyday quality of it. It's not a gold clock that's from 400 years ago, and it's so ordinary and they're placed next to each other. I could almost tie that back to my idea of negative space. If he’d placed them apart from each other, it wouldn't have the same power. But because they're sort of touching, I think it's–

WH: Ordinary. And yet with such profundity, so much pathos.

NM: That’s the thing I have with objects in general. I think it's very easy to love beautiful things, sublime things that have been made, antiques and all. But to respect and love ordinary things is, I don't know, I find it more interesting, really. You can pick something off the street, which is something I might've thrown away, but after time it can become quite important to you as an object.

WH: We can’t talk about the paintings in this show, nor about a sizable portion of your work over the years, without talking about pets, and the way that they really occupy the forefront of your images. The human form often becomes secondary, even sort of auxiliary. Could you tell me a little bit about the affinity, and what it means for you to represent them in your work?

NM: Well, I think it started from when I was quite little. I was always a bit in my own world, a little bit shy and lonely. So I just found a bond and an attachment with pets. And even today, I can't imagine my life without them. I just feel that they're an important part of my life, I suppose. And I like to, when I paint them, I like to try and give them an important part in the composition, which is how I see them in the real world. I think I said previously, I sort of share the Egyptians’ belief that all animals have souls. The only real difference with an animal is that their brain is possibly not as big.

But if you think about the anatomy inside a cat, it's as complicated as a person. It has a heart, has lungs, has everything. And the amazing thing is that a kitten only takes nine weeks to form. That's always an interesting thing, that their body is as complex as a human body. The only difference is really the brain.