Davide Balula: 1. Turn West / 2. Form a Circle with your Mouth / 3. Let the Sun Set In

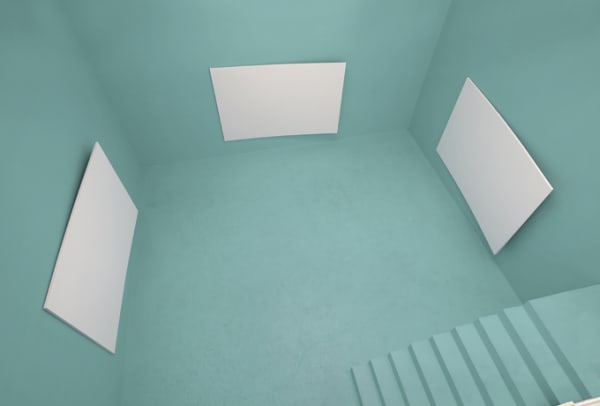

Davide Balula sought permission to enter the Guggenheim museum in New York City during hours that are typically reserved for non-viewing. His intention was to measure the slope and curve of Frank Lloyd Wright’s arcing wall. Visitors to the museum will recall that this architectural element is usually not a point of focus, but rather a plane on which to align objects of culture that become the focal nodes of one’s aesthetic experience. After deliberation, permission was granted to the artist, and he entered the museum. The works on display are manifestations of the artist’s measurements. Each is an exact replication of a fraction of the wall.

Part I: Standing on the Beach

As I type people pass by me in vectors determined by the space we’re all in: the Guggenheim museum. I am sitting on a circular stool with a rectangular computer in my lap. They pass me going one of two directions, up or down, though this looks like left or right. The path they walk spirals, but that’s not obvious in the steps it requires them to move through my visual field. Within five or six feet of me they walk, sometimes closer; occasionally gaining or dropping speed. Very few come to a full stop. I can only witness a fraction of their total movement, and it looks flat, a straight passage—but I know it isn’t. I know a curve can be composed of nothing but straight lines, and depending on one’s proximity to the bend, it is more or less visible. I know it all depends on my (seated) position relative to their (moving) positions relative to the space we’re all in, which is famous for its corkscrew design.

There are pictures by Picasso on the walls today. They are all flat and rectangular; some are thicker than others, a few boast rather sumptuous frames. The incandescent gallery lights built into the museum’s ceiling are approximately a meter away from the wall. They shine down on the Frenchman’s paintings and drawings at an acute angle and cast thin shadows beneath their frames. If not for these shadows shaped like the humps of gently rolling hills, the wall’s curve would be nearly imperceptible to someone standing five to ten feet away and staring straight ahead (at a Picasso painting, for example). It is a bit of an optical illusion: you know the wall is curved, but the moment you focus your eyes on the flat object hanging upon it, the curve straightens out.

I am sitting still in a pedestrian space designed for upwards and downwards flow and I am looking at a stretch of curved white wall. I am staring. It takes concentration and real effort to not be distracted by the Frenchman’s nudes flanking my point of focus. Some passersby observe me observing the wall and they pause and look at the wall and then look back at me and then at the wall again and then they continue walking. What do they see? What don’t they see? What do they imagine they see? The bulbs’ illumination is warm and it spreads across the curved wall like a thing without true edges, fading into shadow before running into an abutment.

An old riddle comes to mind, “what is the longest straight line in nature?” The answer can’t be literal because there are no straight lines in nature. Perspective is the key. The answer is the horizon of the ocean, which like this wall is actually an arc in a much larger circular formation. But it sure looks like a straight line when you’re standing on the beach.

Part II: Tea

An artist and a writer sit in straight-backed wooden chairs at a small work desk. They have made a pot of tea and are looking at images on a computer. The computer is on the desk; the writer’s tea is in his hands. Folder by folder the artist navigates through this digital archive, his tea steaming ever upward at the keyboard’s edge. They are primarily looking at paintings.

“If a painting hangs on a wall, do you think the color of the wall affects the painting?”

“Yes, of course!”

“What color do you think is best?”

“I don’t know about best, but white is pretty standard.”

“Why? If it is not best, why is it standard?”

“I suppose because white is neutral, and because it reflects light well.”

“So the color of the wall is white because white has physical properties that are good for paintings?”

“Basically, yes, but I also think a clean white wall has certain affective qualities on its own. It makes me think of purity, a sanctuary perhaps; white walls make me think of a place where you’d find a monk or a madman.”

“Do you know how many shades of white there are?”

“No.”

“Neither do I, but when I was learning about the Guggenheim’s walls I found out that Frank Lloyd Wright knew exactly the shade of white he wanted, a warm shade called ‘Dove white’. I don’t know their reason, but it’s not the white used at the Guggenheim now.”

“Maybe they ran out! (Laughter) Whatever the reason, it makes me think of how spaces change over time. People who walked into the Guggenheim in the sixties to see Kandinsky paintings would see the same paintings differently if they went today, not because of sociocultural changes, but because the walls are a different shade of white.”

“Yes, I think that’s true. If the space changes, and the space affects the paintings, then the paintings must change too.”

“Right, the Pythagorean theorem as applied to the architecture of art observation. Talking about architecture, can you tell me about your process for making these Guggenheim wall pieces?”

“That was a rather interesting process. I was able to get the blue prints for the museum, but I had to sign many documents promising not to show them or make them public. I made three Guggenheim wall pieces and each exactly replicates the curve and slope of a section of Frank Lloyd Wright’s wall. It required some bureaucratic finagling, but eventually they let me in to the museum after public hours and I used a custom made guage to take precise measurements. It was a little weird, to be more or less alone in this famous museum, measuring the wall.”

“What I like about these Guggenheim pieces is their shapes, they way I imagine them coming off the wall. But I bet from certain perspectives you wouldn’t even notice how they curve. They would just look flat.”

“Yes, flat like the sky looks flat.”

“Did you ever notice how a blue sky gets paler in color nearer the horizon? Sometimes real close to the horizon it looks like a warm white, just like Wright’s Dove white. Maybe Wright’s Dove white was a actually a metaphoric choice, representing that part of the heavens closest to humanity, maybe Wright envisioned hanging paintings on that sliver of the sky just above the horizon…”

“…hmmm. I suppose that’s possible. But if you were to hang paintings on the sky, then you would have to deal with the fact that the paintings would always be changing because the sky would not stay that same color all the time. If you went to view the paintings in the morning, they would look different when you came back in the evening.”

“Wright probably thought about that and maybe he figured the warm Dove white was the closest approximation one could hope for when trying to bring the sky inside.”

“Yes, maybe…What if the colors of the walls of a gallery in California were to gradually fade into that color, day by day? It would mean something different; it would be like transferring the walls of the Guggenheim into the walls of the gallery.”

“You’re talking about a slow fade into Dove white? That’s interesting, but how would visitors be able to see that? What would it fade from and how would they know they were essentially standing in the midst of a paint-driven symbolic transformation of architectural space?"

“Good question. Maybe I’ll use the California sky as a template. You want more tea? I could use a refill.”

“That sounds good. Thanks.”

Part III: Like a Childhood Memory

You enter this space knowing it’s an art gallery. Maybe you’ve been here before; it seems familiar but you can’t recall any previous visits. You can imagine them, but you can’t really remember. It’s the details you’re questioning. You can’t be sure if you made them up or if they’re authentic. Like a childhood memory—you don’t actually remember that day in the yard, but you’ve heard the story so many times that you have vivid mental images of the entire ordeal. You could tell the story like you remembered it yourself, and you have.

You let the door slowly swing shut behind you as your eyes play across the white walls, the ceiling ribbed with track lights and the parquet floor. You’re scanning the room, visually skimming the surface of the space like one of those long legged water bugs that skitters across the surface of a pond or a lake. You aren’t questioning anything right now; you’re just taking it in, accepting all this visual data as it comes. And it’s not that hard for you to do because you feel like you’ve been here before.

When your eyes make their first pass over the objects mounted on the wall you attend to them as if they were part of the space, though you know they are not. They are not part of it; they are in it, conditioned by it. You scan them; you take notice. They do not simply represent your reason for being here; they are your reason. You came for them, to see them, to think about them.

It’s only when you begin to give them your attention that they truly take shape in your mind. You’re gazing now; you’re absorbing details; you’re beginning to scrutinize. You think of the gallery as a vessel for the art works and you think of your mind as another kind of vessel that the artworks have begun to fill.

The artworks make you think of Modernism. They make you think in terms of formal compositions, geometric correspondences, abstract values. You have learned to appreciate the elegance of an arced line and you exercise that skill. Your powers of association are equally adept and you find yourself mentally citing instances in nature that correspond to the artwork in formal terms. You haven’t read the press release yet, nor do you know the titles of the works on display. You’re taking them in as purely physical facts and you wish in a profound way that you could run a finger along the object’s edge. The craftsmanship is impressive. You appreciate that.

What is the emotional content of these works? There are three of them, three objects total in the room, and they are quite similar though they’re not identical. You have a thing for numbers and the number three carries particularly heavy symbolic weight. You were raised Christian, you grew up with the holy trinity, but you also grew up with a scientist for a father who taught you about Pythagoras and how the principles of triangulation can be applied to processes of navigation. You acknowledge these connections and let them fade. They are yours; they don’t belong to the artwork. Again, you ask yourself about the emotional tenor; what do these works make you feel?

It is complex, and because you can’t name a feeling the way you can name the color of the artworks—white—you consider the affective quality of the works’ character. There is a hint of ambiguity, an enigmatic sense to the objects that you find intriguing and mildly titillating. On some level this excites you. When you were younger work like this could arouse anxiety and fear, because you worried that you didn’t understand, that you were not intelligent enough to understand. You don’t worry about that anymore. In fact, trying to understand an artwork seems a little naïve to you now and works such as these, which might have inspired that kind of anxiety, mostly reinforce this notion. They remind you of your personal growth and that makes you feel assured, comfortable.

Eventually you read the press release, the accompanying gallery literature and the works’ titles. This removes much of works’ mystery. You know the origin of their form and knowing this one fact seems to make tremendous difference. It opens up new fields of conceptual possibility. You’ll call your friends and tell them about it when you get home, you decide.

- Charles Schultz

Davide Balula was born in 1978, and currently lives and works between Paris and New York. He has held solo shows at Frank Elbaz, Paris; Fake Estate, New York, and Confort Moderne in Poitiers among others. He also recently staged performances at Night Gallery, Los Angeles; Pompidou Museum, Paris; and Performa, New York, and was part of numerous group exhibition including, the Pompidou Museum, Paris; Eleven Rivington, New York, Thadeous Ropac, Paris, MassMOCA, MOCA Miami,MAC/VAL, Vitry Sur Seine, Songwon Art Center, Seoul, Fondation Cartier, Paris, Bielefelder Kunstverein, Germany. This exhibition will mark his Los Angeles solo debut.

This exhibition is part of Ceci n’est pas inititiated by the Cultural Services of the French Embassy in the United States in collaboration with the Institut Français, with the support of the Alliance Française of Los Angeles and the French Ministry of Culture and Communication.