Marius Bercea: Concrete Gardens

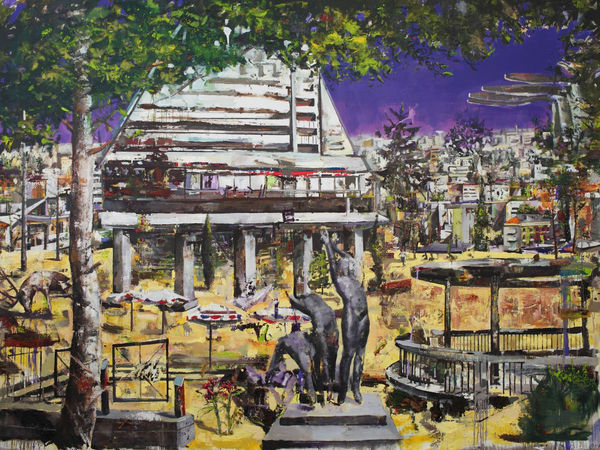

The city square is deserted. There's no one strolling past the columns of the former municipal building, no one on the bandstand. The heat that pulsates on the canvas is keeping everybody at home in this languid summer evening. The modernist pyramid, vaguely redolent of Le Corbusier and Oscar Niemeyer, is a monumental relic of the failed utopias of the 20th century. Imperfect Pearls Shimmer at Dusk (2011) could be in any nondescript ex-USSR city. Although Marius Bercea does not specify the location, the artist is clearly picturing a place lived in, used by its invisible inhabitants to the point of exhaustion. The three diving statues invite the eye to the vast sand expanse, absurdly tropical with its exotic flowers and white promotional umbrellas. There's a distinct yearning for escape from this place saturated with memories — fed 24/7 by the lurid billboards gleaming on the horizon.

Bercea belongs to the generation of Romanians who grew up under Ceausescu's regime, and saw their country's rapid transformation after the dissolution of the Communist Bloc. In some of his earlier paintings, the artist tackled real and imagined childhood recollections: the formulaic school photographs, games, and picnics of faceless kids, wrapped in the yellowish, noxious air that hung over Eastern Europe after Chernobyl's nuclear disaster. With this new series, described by the artist as a "collective urban portrait," Bercea deals with what happened immediately after 1989, with the arrival of Western capitalism; neon slowly taking over the cityscape, its fluorescent hues slapped on the decaying concrete, the shifting sense of what is normal, what should be aspired to, and how it could, or should, be obtained. Although it eschews direct narratives, Imperfect Pearls Shimmer at Dusk evinces a sense of being in flux. Advertising blurs progressively emerge from the brushstrokes' rich interlays; Romania's transition is happening on the canvas under our eyes.

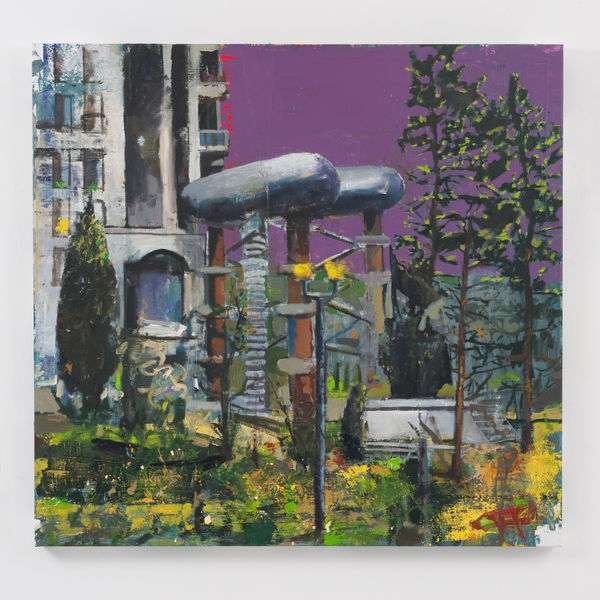

Bercea bathes his built-up environments in the suspended atmosphere of twilight: dawn of an era, dusk of another. He uses these warm, vaguely threatening skies for a forensic study of light and its effects, walking in the footsteps of the great landscape painters J. M. W. Turner and Claude Monet. The heavy purple offsets the street light boxes' electric glow and the lush emerald leaves quivering in the breeze; it enlivens the dusty grays of the buildings, temporarily smoothing their fast-coming obsolescence. Most of the edifices presented in this series exist somewhere in the real world, at least in part. Bercea has collected different bits of buildings, combined and reconfigured them to create this recent-past dystopia, a condensed version of all his sources. With its top lost in the heavens, the pyramid in Imperfect Pearls has something of a Tower of Babel — an overbearing icon of men's folly, past and to come.

Critic and curator Jane Neal describes Bercea's painting as a kind of archaeology, a process of navigating layers of time, space, colors, and semantics encrusted on the canvas. While the conceptual background of each piece in this new series is too pregnant to ignore, it's also a ploy for the artist to stretch further his ongoing exploration of the medium, his tireless testing of Albertian perspective, and experiments with the dilatation and refraction of light on the picture plane. Bercea's practice is decidedly figurative, and yet it also freely taps into a gestural tradition more readily associated with abstraction. Dotted throughout the images — indeed making the images — countless impetuous impastos stand as so many pieces of bravura, only fully appreciable up close. These idiosyncratic touches reinforce the sense of the artist's presence; his personal experience is rendered palpable through the materiality of the paint. But Bercea always aims beyond intricacies of the specific. In these canvases, he recounts the history of a part of the world as it struggle to find its place in a new geo-political landscape.