A transcript of Christine Sun Kim in conversation with senior director Gan Uyeda on her show, Trauma LOL. With ASL interpretation by Francine Stern.

Gan Uyeda: To start, Christine, maybe you could take us back to where this exhibition started, some of the early ideas that were guiding you. What were some of the starting ideas that were fueling this show?

Christine Sun Kim: This show really started with my performance of the national anthem at the Super Bowl in February 2020. I had been to five different cities in a single trip in February leading up to the performance. The last day before the quarantine I had another opening in Berlin. So, I had done all this traveling, had been very active, very public. When quarantine started, it left me feeling a bit disconnected. It had been such a wonderful month of work. It was just so full on. And then to get here, locked inside, the pace was just a 180.

The rhythm of my practice and making work felt completely disconnected—I wasn't making any new work and hadn't for a long time. I felt like, should I continue working? Where should I be right now? And as an Asian person in Berlin, I faced quite a bit of negativity because of where COVID originated. So I was thinking about all this trauma that was building up, and trauma that I’ve faced over the course of my life. I'm a woman, I'm a Deaf woman, I'm Asian, all this trauma on top of trauma. It just really started to unravel. And that's how it began.

Uyeda: When I think back to the show immediately prior to this, at the MIT List Visual Arts Center, those drawings are very cohesive with one another. There's one format that you're following across those drawings, pie charts that are depicting different kinds of emotional and psychological experiences. To take that turn towards this show, I see you working with a lot of different formats. Do you think that there was a lot of experimentation going into this show? Searching for new kinds of rhythms, formats, information systems?

Kim: Definitely. 2020, you know, I had so much time and I was looking at so many things. I have always been interested in infographics. Something that's easy to communicate in any language, to communicate any idea anywhere in the world at any time. There are no barriers with infographics. If I express something in English, not everyone knows English. So to use these infographics, these designs and different shapes, it's an easy way to communicate. It almost mimics gestures or body language, which anyone could essentially understand.

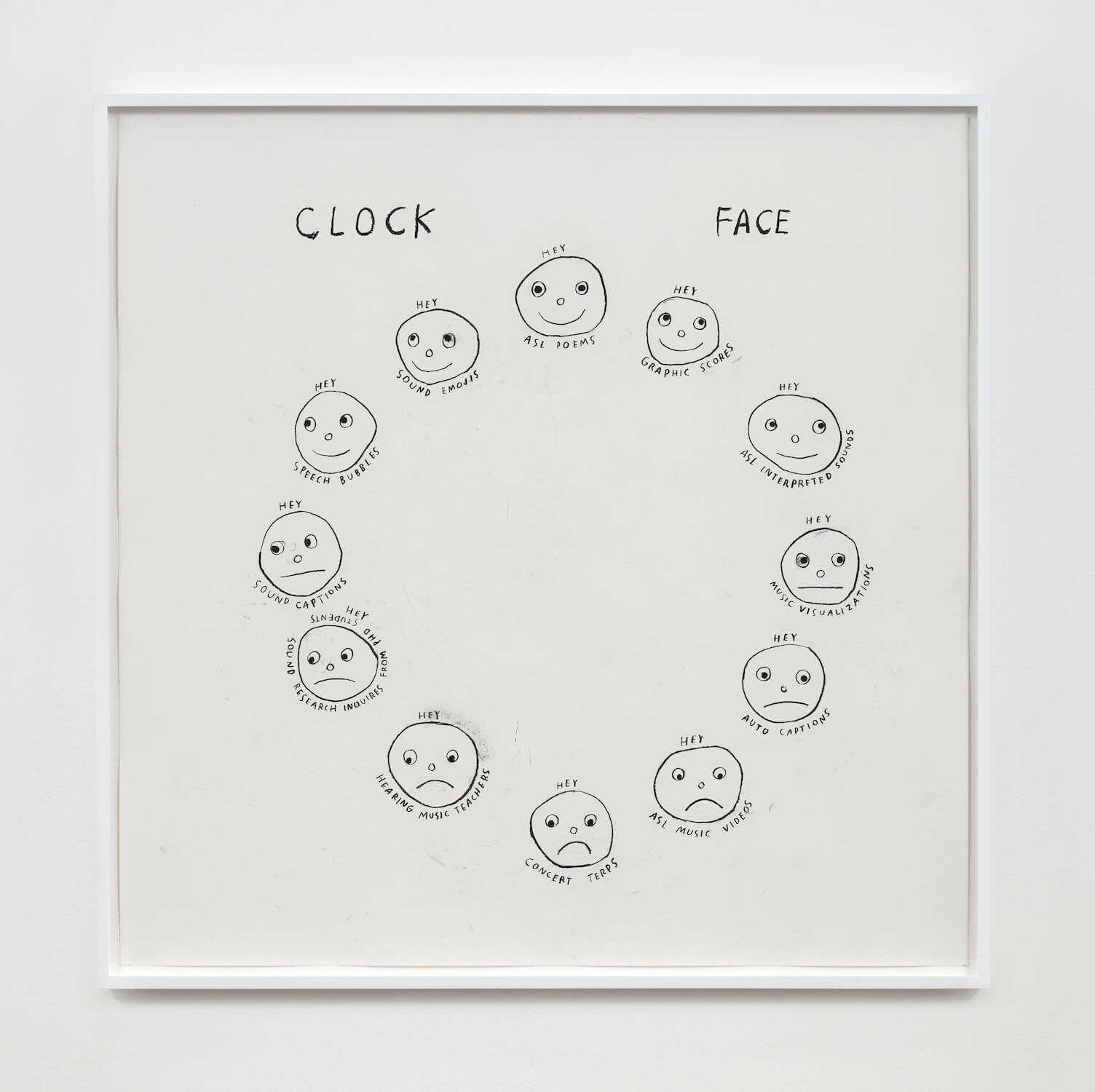

Uyeda: I think about all of the examples of clocks in this show, definitely a reflection of where we were in 2020 and where we continue to be, where time is a very strange thing for us. The exhibition is in two rooms, and the first room is in a lot of ways about American Sign Language, its structure, its rhythms. The first drawing that you see when you come to the room is this one, Clock Face. Can you tell us about this infographic, where that comes from? And maybe we can unpack a few of these smiley faces.

Kim: I think Clock Face was a great way to express my judgmental face or my personal opinions, the amount of emotion, the amount of anger. I have a lot of opinions about things, and I wanted to convey the gradient of an opinion or an emotion. So I decided to have the faces go from happy to sad. The happy face at the top is me taking my hat off to ASL. Visually ASL is so much more prevalent now, like with meetings or something on TV, press announcements, movies, ASL is so much more present. There's a lot of Deaf people kicking ass right now. It's amazing. ASL poems, that's the most respected thing in the Deaf community. It's like an oral tradition. It's something that you can pass along through storytelling. ASL poetry is a very rich, very deep part of Deaf culture.

Moving down the opinion spectrum, you have ASL-interpreted sound. That's when you have to depend on the interpreter, their perspective of sound, which I find limiting in a sense, but it's still accessible, so that's okay. Moving down further: music visualization. People often look at me and say, it's a visual translation. Yes, I used to do that in the beginning of my practice. The translation could be a visual imprint of the sonic frequencies, things like that. Very straightforward. But I got bored fast with that. I could relate more to social reactions, social norms, language, and concepts having nothing to do with visual music. That’s why the mouth is kind of flat across. There's neither a smile or a frown.

Further down the clock there’s ASL music videos. I don't mean to hate on that. I don't want to hate on signed music videos, but ugh... It's not natural to me! It doesn't feel great. The ASL is interpreted from the English, let's say from spoken language, written English or a song, and then to sign it, it's not natural. And yet it holds a lot of value online. Hearing people love that shit. So many likes! But to me, it feels like hearing people performing for hearing people, or at the most translating across the surface. But an ASL poem originates from ASL, it doesn't originate from English, which means that it is great for my eyes, it’s pleasing. ASL music, I'm like, okay, I enjoyed it. But it's a little depressing sometimes to see that it has so much value in the media and Hollywood. Hopefully in the future, there will be more room for Deaf poets, Deaf poetry from ASL, not originating in English.

Uyeda: I think that really connects to the work that is next to Clock Face. Here we have I Walk, I See which is a trio of works that maybe you can speak about. I wanted to get into the relationship here between lullabies or children's songs and ASL, and maybe link this also with the work that the Smithsonian Museum of American Art acquired called One Week of Lullabies for Roux and talk about that relationship. But why don't we start by you describing exactly what we're seeing here.

Kim: I wanted to take my hat off to a group of people who make ASL media for children, called Hands Land (you can find it on Amazon). When my daughter Roux was born—she's now three–I wanted to sign stories and lullabies with her. I never really grew up with full access to ASL. I always had to take it from English, but I didn't feel like it was a natural thing. So I wanted it to be very natural for her. One of the Hands Land founders, Jonathan McMillan, who's a very good friend of mine, created all these beautiful videos that were strictly based on ASL structure. English has its rhythm and ASL has its rhythm as well, which is entirely different. And there's one song that I think about that I always signed with Roux on the train called "Daily Walk." In the song, each day of the week is based on a different handshape. On Monday, it goes I walk, I spot (meaning I see) a mouse scurrying by. Each of these signs uses the one-handshape. Then Tuesday uses the two-handshape, and so on.

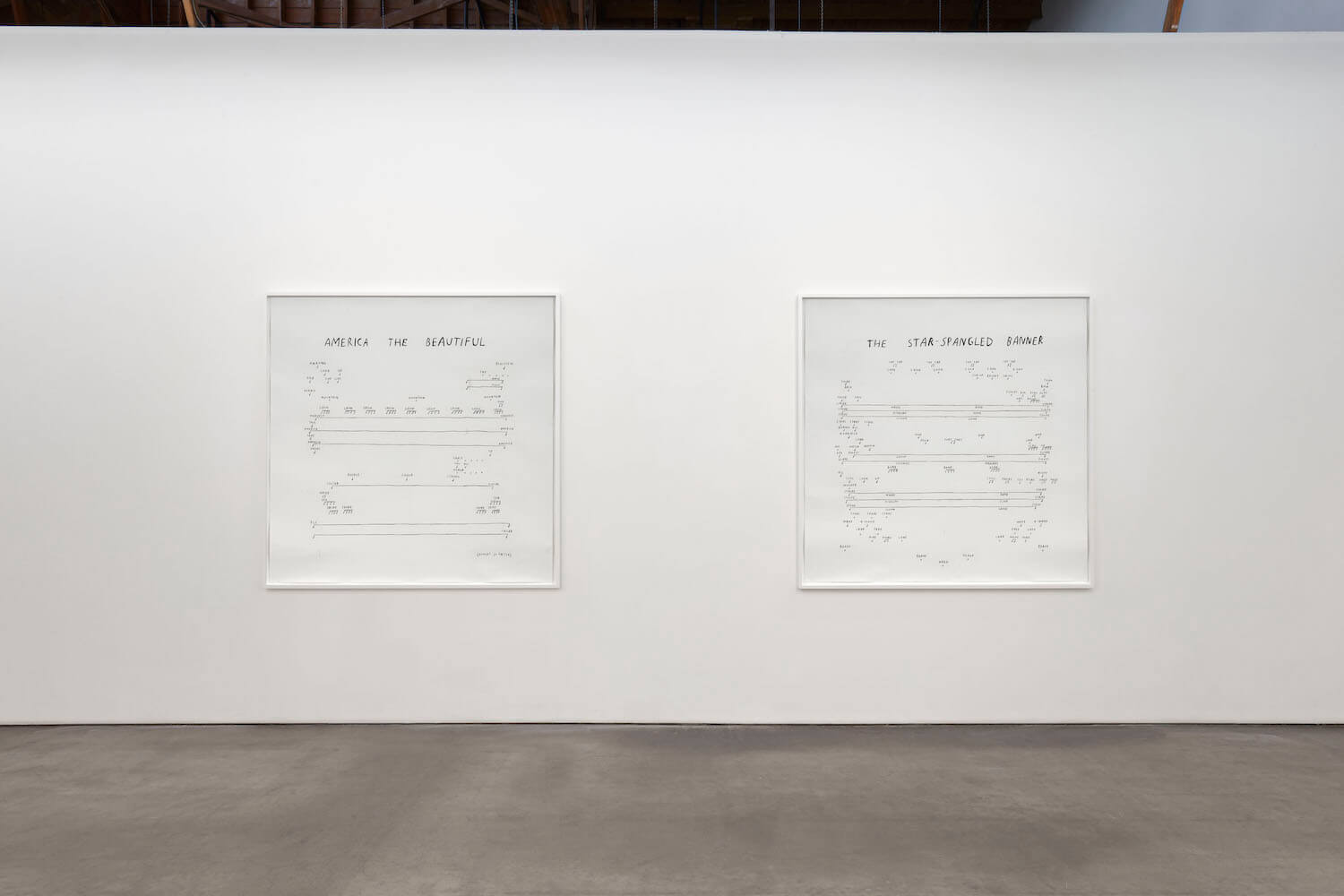

Uyeda: Language acquisition is a really interesting undercurrent throughout the show that we can get to a little bit more later, but the fact that your child is in this language acquisition moment, is definitely underscored in the exhibition. So staying on music, let's switch over now and look at the opposite wall where we have America the Beautiful and The Star Spangled Banner.

Kim: These are notational drawings of ASL translations of the national anthem and “America the Beautiful.” There were three steps in the process of making them. First, there were the English lyrics, second I translated the lyrics into ASL, and third, I translated the signs into ASL gloss using English words and put that on paper. I do want to explain a little bit about ASL gloss, which is a technical writing system. It's the best way to capture each sign and notate it on paper by a word. In some ways a glossed sign is similar to a musical note, where you are trying to envision sound and capture it and notate it on paper. So these notation drawings use both ASL gloss and musical notation together to capture my performance of these songs.

Uyeda: The America the Beautiful drawing here notates what you performed at the Super Bowl, but the next piece, The Star-Spangled Banner is slightly different. You made a small but important adjustment here compared to what you performed.

Kim: Absolutely. The two drawings in this show are actually a second version. I made a first version last summer which I showed at a museum in Berlin. After I finished the drawing, the Black Lives Matter protests and the racial reckoning with historical American figures began to take hold. I was reading and reading and I found out more about Francis Scott Key, who wrote The Star-Spangled Banner. He was such a racist! He fought for the right to keep people enslaved. I felt so conflicted—I signed that song, I made a drawing with its lyrics. I was like, what does it really mean? I'm a huge believer in using my platform in the best possible way.

It had felt very political for me to take part in the Super Bowl. I was happy with the opportunity, especially because I could publish an op-ed in the New York Times the next day expressing my thoughts on why I used the NFL’s platform. I wanted to make sure that people understood where I stand. And that's the same thing with The Star-Spangled Banner. So I decided to notate it. I made a new version of the piece—this is the one in the Ghebaly exhibition.

There are four stanzas in The Star-Spangled Banner. The first one is the popular one that's used as the national anthem, but the other three are essentially ignored. When I read them in full, I couldn’t believe how full of anger they are. So I took some of the words and rearranged them and incorporated them into the middle section that represents the banners. I was really happy with this new version instead of just getting rid of the idea of representing the anthem. I felt like there was still something to show, to express. Is this the best solution? I don't know. I might even make another new one.

Uyeda: It is a beautiful metaphor for these underlying histories of racism and systematic oppression that exist in this country. I mean, this is our national song and this history is a part of that song and most people on the street don't know that. So I love the fact that you excavated this and put it front and center.

I wanted to point out an example of other cultural translations that you're making within this translation that you did. Where the first line of the anthem is "Oh say can you see," instead you change the “Oh” to “tap, tap, tap, tap, tap, tap, tap, tap.” So it's a way of getting attention by tapping on the shoulder rather than having an oral call.

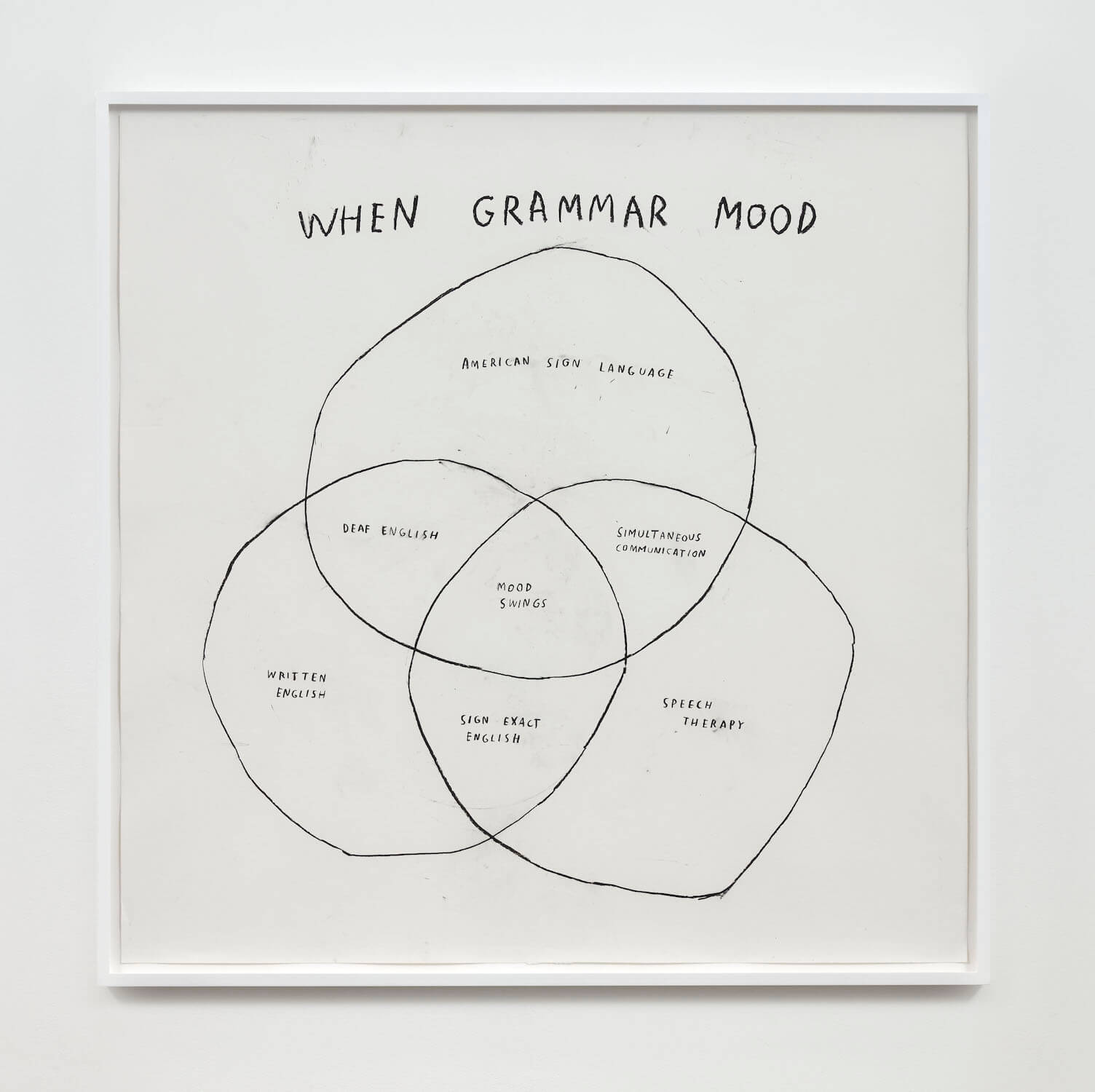

Let's keep swinging forward. We have two works that are really about the kind of structure and the linguistic dimensions of ASL and its relationship to English, especially with this one, When Grammar Mood.

Kim: Yes. So I used a Venn diagram. I love the idea of the overlapping, the intersectionality of this kind of chart. The overlapping is very situational. When I was growing up in Orange County, California, I used SEE sign language, Signed Exact English. So you sign each word using English sentence structure and grammar. ASL has a different structure and syntax, but in SEE sign, you would sign, how / are / you / question mark, whereas in ASL you would sign HOW YOU with the question indicated on your face. They are different languages.

So when I was growing up, that's what I used. Many hearing educators believed that was the best way to teach English through sign language, by using SEE. It didn't really sit right with me, and I used it for many years. The next overlapping section says simultaneous communication, or SIMCOM. It’s the idea of signing and talking at the same time. The last overlapping section is Deaf English. When I’m writing in English, sometimes I switch things. If I'm writing really fast, I kind of lose some of the tenses. Some of the syntax, it gets lost. That's Deaf English because ASL is the language I think in first.

In the middle it's mood swings because I kind of feel like one day, my English is really good, and one day my signing is really good, but then other days not so much. I feel like there's so many different modes that are being used, and mode switching brings code switching—this idea of situating your use of language within certain social contexts. Sometimes, it can leave me feeling a little lost.

A side note about SIMCOM. Currently, my daughter attends daycare. It's bilingual, bicultural daycare. I'm struggling right now because they're all big on SIMCOM or simultaneous communication and their perspective is they think it's cool. They can sign and speak at the same time, but think about it, you can't speak French and Korean at the same time. One language always suffers. I struggle with that because there's lots of hearing classmates there, but they don't sign because they can talk and they have perfect access while the deaf kids in the daycare don't exactly have full access. So I've been thinking a lot about that and SIMCOM, and I relate that to another drawing in the show as well, Competing Languages.

Uyeda: Let's move into the next room and I want to start off here with your mural, which is a kind of anchor to the show. I was thinking about this piece and I decided to tally up all of your large scale mural or billboard projects just from the past couple of years. I got to 13 different projects at this massive, billboard scale. I want to ask about scale as a medium and how you think about size and visual access, and maybe even the language of advertising. How do you think about using scale as a medium?

Kim: How that started was several years ago, the Whitney Museum in New York asked me to do a billboard. And I think I had just given birth and I didn't have a lot of time. I didn't even have the mental energy, but I was looking at some old drawings and I thought, can that work, could that work? So there was one called Too Much Future. I scanned it and sent it to them and they put it up as a billboard and I thought, wow, wait, my drawings, not all, but many of them can really work on that large scale. And it was so exciting to me. I thought, Oh, my drawings have a lot of possibilities on paper and then on a billboard or on a wall or a larger scale. So that kind of opened the door. From then on, I had a lot of invitations for large scale billboards or murals. I feel that adapting a drawing to different scales depends on the concept. It depends on the lines. Are they thick? Are they thin? Some works can work both on paper and in a large scale, for example, this one. It was Gan's idea to choose this one to scale up, and I think it looks so great.

Uyeda: This drawing really interests me. You rarely represent the actual hand in your drawings of signs. Many times you notate them as lines that are moving or as musical notes. But this one is the actual hand making the motion. I wanted to track that back to this earlier billboard that was in Tokyo in 2019 called Let's Take Turns. It also depicts this sign: Your turn, my turn. Can you tell us about the transition from the use of the sign in Let’s Take Turns to Turning Clock?

Kim: This sign represents my turn and your turn. So it's my turn. And then it's Gan's turn or Francine's turn, or it's everyone who's participating. It's all of your turns. Gan was right. I don't often use the hand shape in my work because when I started my career as an artist, everyone expected that, Oh, you're going to draw hands. You're going to draw signs. And I thought, no, I didn't want to follow along with that expectation of what my work should be from my own outside community. But now I have started to do a few, partly because I feel my platform has already expanded. So I feel as though it's comfortable and safe to experiment with hands—I’ve already built my work outside of those expectations and now I can play with them.

I was thinking about how we would take turns because time as it was going on and on and on during quarantine. I was thinking about responsibility, and the responsibilities that fall on small and marginalized groups. Oftentimes they're doing activist work, that’s great, but it's not healthy to go nonstop. And it's not sustainable for us to fight and fight and fight all the time just to get our basic rights or needs met. Just our basic rights. So I feel like other people should take their turn in being responsible. Those who built the system, those who set up the social norms, they need to make things easier for us. And so I felt like, okay, it's your turn. I'll do my work, but it's your turn too, okay, I'll do some work, and then there's the turn-taking going around the clock. It also parallels what I experienced with my partner, taking turns with caring for our daughter. It's your turn, I'll work. And then it'll be my turn and you can work. Then it'll be my turn. So shared responsibility there as well.

Uyeda: Yeah, exactly. And in the context of protests, it's really important to think about this, that right now I'm showing up for you and later that can be reciprocated. We have to have the shared burden and the shared responsibility of that, of showing up for each other. So I think that's really important. Christine, which work would you like to focus on next in this room?

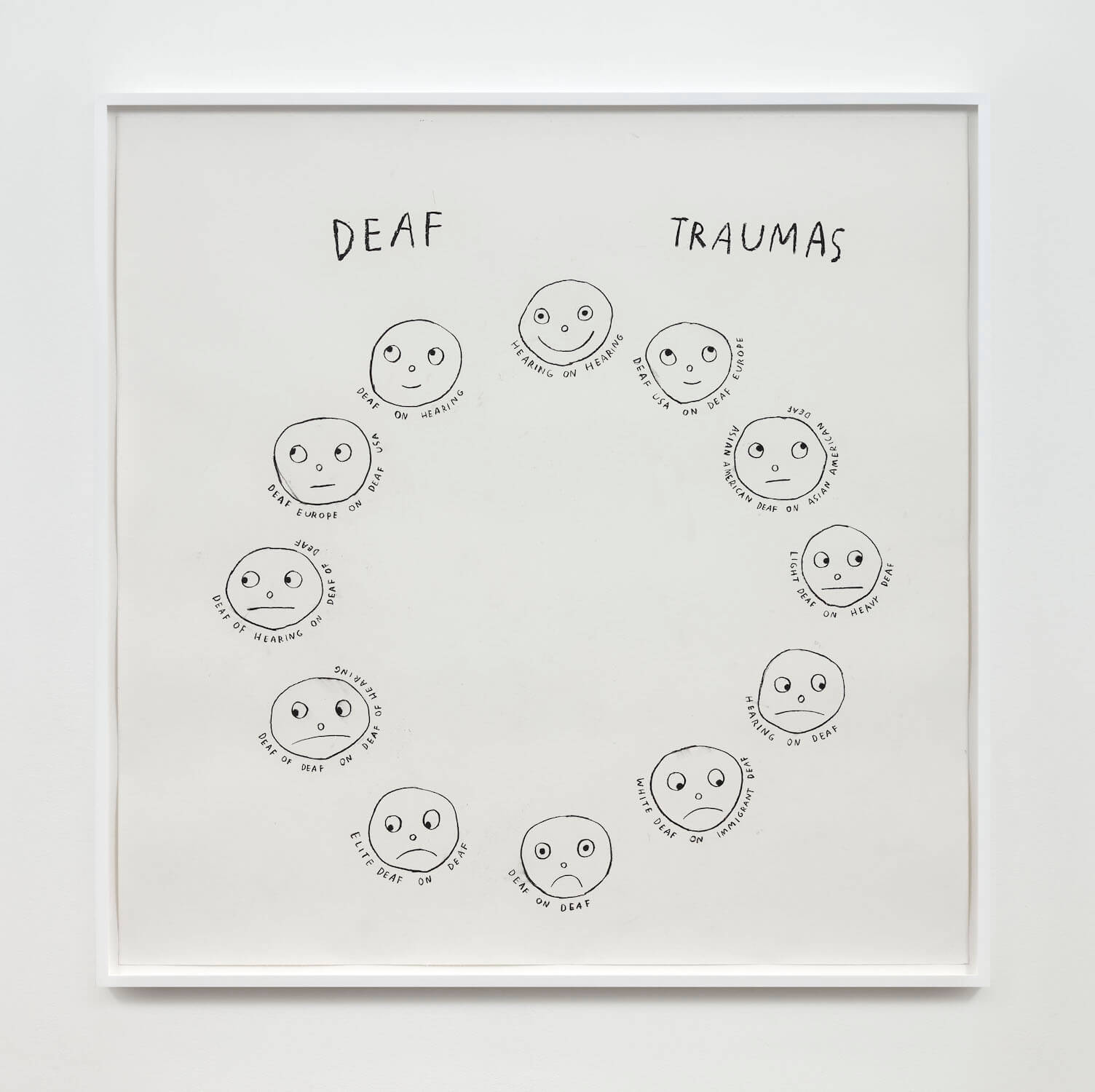

Kim: Deaf Traumas is one of my favorites. Last year with COVID and the Black Lives Matter movement, there was so much heaviness and emotion. And I was looking at a Facebook group and the Deaf community on Twitter, and there was a lot of drama and chaos and I was following all of this stuff. I started to feel like, wow, the Deaf community is so complex. There's so many different identities. Everyone has different access to language, access to educational resources. There's no standardized access or experience. So what I experienced personally related to Deafness is what I expanded on.

Kim: I'll give you a few examples from the drawing. Here it describes “Hearing on Hearing” trauma. Obviously that’s a smile because it relates to how almost everyone in the Deaf community has that story of when you first realized, oh, hearing people are not that smart. For me, I was in New York, there were lots of strangers I met that were actually dumb, acting messy, being foolish. That was when I had a moment of oh, they’re just like us. And that felt good because when I was growing up, hearing teachers, hearing adults, they were always positioned to “know what was best” for me. They would decide things for me, and this is not just personally, this is about laws and rights. So I was able to rise above that inferiority complex.

There’s another face here that says “light Deaf on heavy Deaf.” Light Deaf meaning, maybe you grew up deaf but don't identify that way culturally. Or maybe you can talk or wear hearing aids or sign only a little bit. Whereas with “heavy Deaf,” you grew up going to a school for the Deaf or a Deaf residential school, you’re intergenerationally Deaf, you fully take part in a Deaf identity. And sometimes, there's oppression from one Deaf group to the other. Sometimes that can be white Deaf on immigrant Deaf. I've seen that myself; I was born here, but my family immigrated. There's a strong white generalization among Deaf people in America. There's maybe not so much room for us. I've seen a lot of trauma there.

And then the last one at the very bottom with the big frown is Deaf on Deaf. There's a difference between hearing people oppressing Deaf people—that's somewhat expected. That's kind of the norm, that's the tendency. But Deaf on Deaf, that hurts bad. I would never expect oppression from my own Deaf community. Moving down the circle in the drawing, the conflicts are pretty heavy traumas.

Uyeda: I think this work is so important in breaking apart the idea that Deaf culture is one thing. That there is only one way of being Deaf. The drawing really focuses on these internal struggles, even within the Deaf world. But as heavy as that idea is, you still make room for humor within the drawing. That brings me to a question about humor. How strategic is your approach to the use of humor. How much do you think of it as a tool?

Kim: Growing up, I was never a funny person. I didn't view myself that way. I had my bubble, I had my Deaf friends, my Deaf sister, I had Deaf boyfriends. It was a very safe little bubble. As I got older I started to leave that bubble once in a while, but still I would always go back to the safety of my bubble. Eventually I wanted to make art and I wanted to start working professionally. I had to break out of the complacency of my bubble, to start associating with the hearing community. I thought, how can I put myself out there without filtering and softening my ideas? I’m not going to go halfway. I have to go all the way and kind of meet people over on their side. And humor helps. It puts people at ease. People feel much more comfortable when there's a little humor involved. As I grew as an artist, I could see that showing up more and more in my work. My work tends to be a little heavy, but I don't want to alienate people. I want to figure out how to take a heavy idea, then layer it with humor in order for audiences to connect first to the humor and then to really understand and access my ideas. Maybe this layering with humor is a coping mechanism for me.

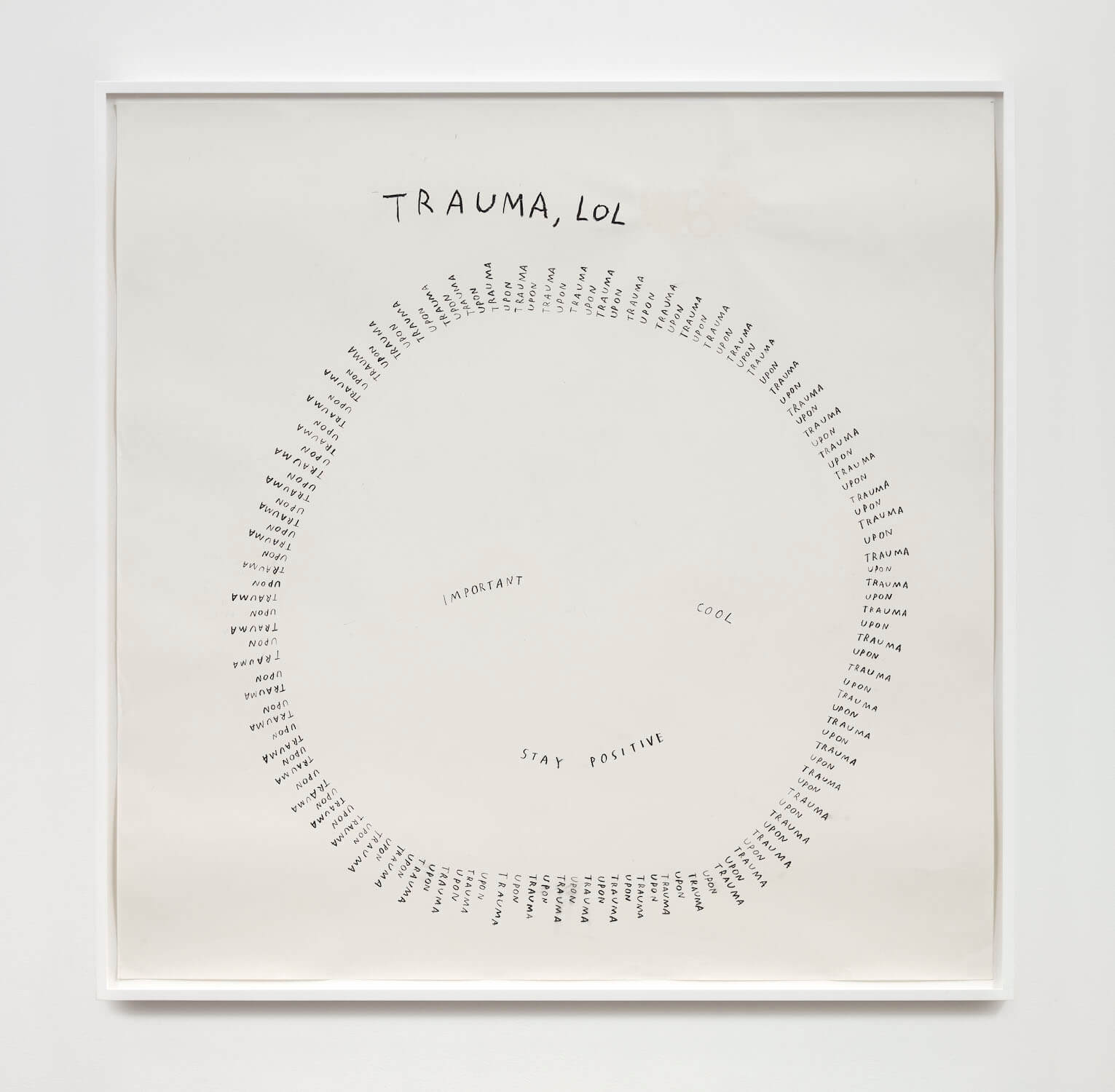

In terms of coping mechanisms connected by my Deaf experience, this drawing, Trauma LOL, is probably my favorite.

Kim: I decided to make this one the star of the show, the title piece. I was thinking about how there are two kinds of trauma. There's, let’s call it single trauma. For example, something very direct and clear, you know, losing your arm, a car accident, a sexual assault, something that you can communicate to people who have no experience with that trauma, but can still understand it. And they can see it very clearly. It's something physical, tangible, understandable. The second kind is plural trauma, and this is years and years of built up trauma. It's not clearly physical, it's not visual. It's something that's harder to communicate and describe to those people who haven't experienced the same type of trauma. For example a deaf child who is denied access to sign language. They will struggle with learning. With work, family, relating to people. It's years and years of denied access to education, language deprivation, it's trauma upon trauma upon trauma upon trauma. So this goes around and around, kind of like a clock.

About the title, I didn't want people to think that I was minimizing or making light of the trauma. No, this is a real thing. For me the comma is a very active part of the title: Trauma - comma - LOL. There is a separation, a response over time. LOL as a response very much comes as a reaction to being shell shocked from this trauma. Trauma happens, and what do you do? You can address a small trauma, you can deal with it. But trauma upon trauma upon trauma? That starts to become LOL.

Uyeda: Or at least that's the coping mechanism. That's the way that you can address it when the barriers that we're talking about are truly systematic and very much beyond the realm of an individual person. There is a kind of absurdity to it. So you laugh.

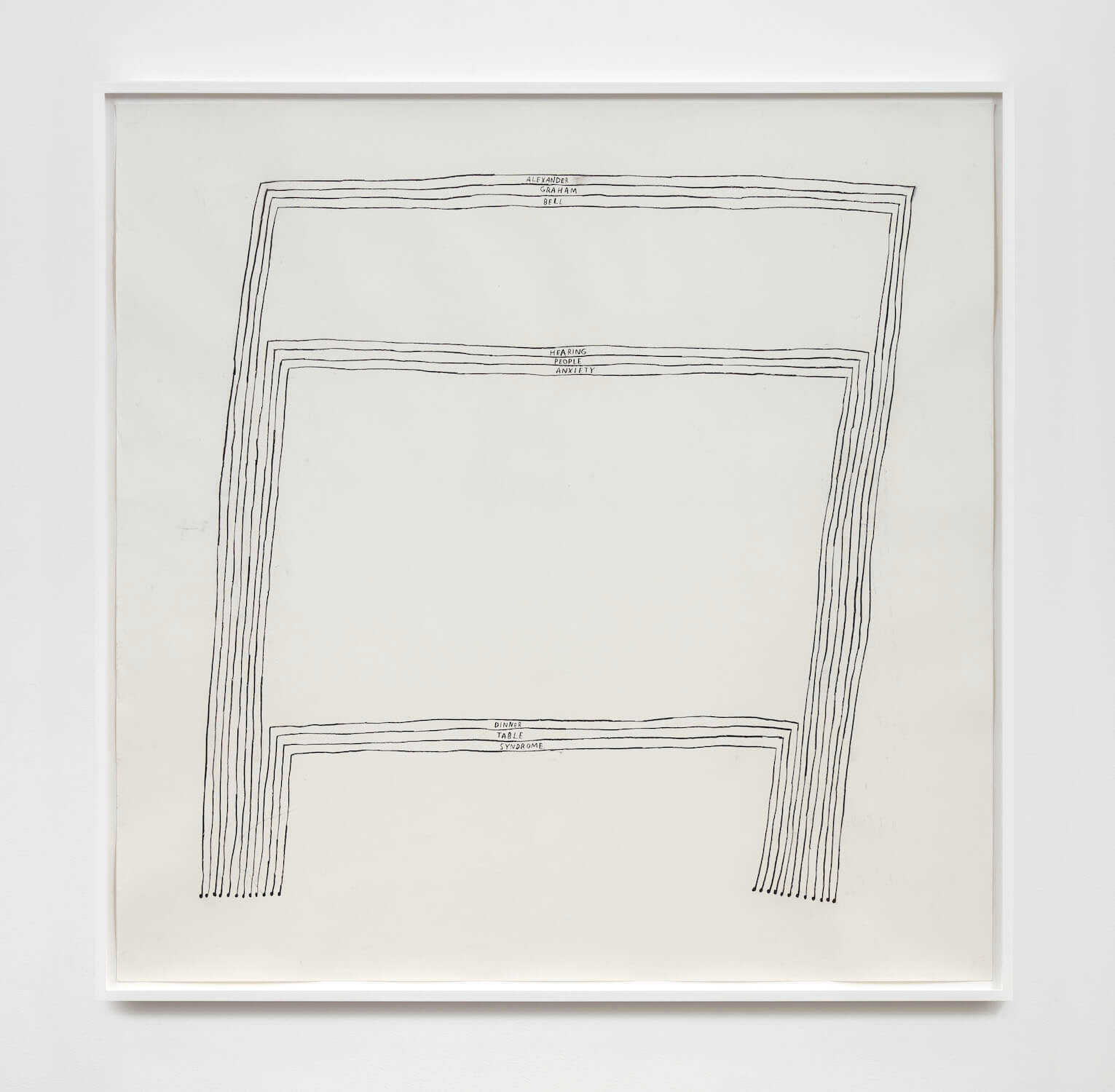

Well, why don’t we start wrapping up with this work, Three Tables III, which is starting to push your use of musical notation into an interesting representational space.

Kim: This is a drawing of three stacked tables each made of three musical notation beams. I embedded text in each of them: Dinner Table Syndrome, Hearing People Anxiety, and Alexander Graham Bell. With Dinner Table Syndrome, if you want to understand how a Deaf person experienced a relationship to their family, just go to their dinner table and see what that looks like. Do the parents and siblings sign? Do they talk sometimes? Do they only talk? And the Deaf person is sitting there isolated and excluded from the conversation.

It comes back to my experience as part of a family of immigrants. My parents had a strong belief in the importance of showing up and eating dinner together, to bow and eat well, drink well, be together. Growing up, I understood that that was important to them, the physical togetherness. But at the same time, oftentimes when the larger family was around, aunts and uncles and cousins, there wasn’t a lot of signing. I would say, Hey, could you sign please? And they’d say, I love you, but then they would still just continue to talk in front of me. Being physically together and eating together wasn’t enough. I wanted communication, because communication equaled love.

Hearing People Anxiety, HPA. This is kind of a new term, but it’s come up a lot with younger Deaf people. It means, like if you go to a meeting of a hearing group, or to a restaurant or a party, and there’s some amount of anxiety. You have to go in and beef yourself up as a Deaf person when you’re surrounded by hearing people. I still do have anxiety when I go to a big party or a gathering. My heart beats a little faster, and I have to put myself out there and really roll up my sleeves. It’s a lot of work.

And last, on top, is Alexander Graham Bell. Everyone knows that he invented the telephone. Technically he stole that idea, but that’s a story for another day. Bell’s father was obsessed with oralism, and teaching Deaf people to speak. Bell himself married a Deaf person, and his mother was Deaf, but he didn’t sign. He believed that the best way to integrate into the hearing world was to speak out loud. I’m a big believer that you should have full access to at least one language from birth. That one language will be the one you identify with and have access to, right from birth. Then you’ll be fine. You will learn everything else, it will fall into place, but in the beginning you have to have that one language. With an exclusive focus on oralism, you are denied that one language at birth.

Bell had huge fame and power, and he successfully convinced people at an international convention in 1880 to remove sign language from Deaf education as a whole. That was a dark period for us as a Deaf community. Today, we sign, but there’s still that influence that extends into the present. It still exists. That is the top table, the big powerful table, the one with the most influence.

Uyeda: Okay. So let's turn to some questions. From Shue Her-Sturm: “Speaking of taking turns, do you have any thoughts on how hearing advocates, not in leadership positions at cultural institutions, can support the arts for the deaf community, encouraging more accessibility and appreciation, et cetera. Is that even a need at this time?”

Kim: I went to two art schools, so I've seen firsthand that it's a little tough as a Deaf person to get feedback from teachers or visiting artists. Often it's very on the surface. They don't want to touch the issue. They don't want to be negative, but how can I really grow and develop as an artist if they're not honest with me? I've seen this over and over. Oh, that's cute. That's cool. That's good. It wasn't enough. I didn't feel enough of an honest connection or feedback or encouragement. They would just bring the interpreter and then that would supposedly solve the problem. But the Deaf community needs more than just interpreters. They need involvement, they need an investment. There should be someone following up and following through and being present. The Deaf community is an oppressed group. As an artist at my level, there's not many other Deaf artists that I can count with both hands. So I think it's responsible to have advocacy and more involvement, maybe more one-on-one mentorships. Don't make them feel guilty for asking for accommodations or access.

Uyeda: A question from Ezra Benus: “Can you share more about the choice to use charcoal, and not paint, ink? Ever consider working with color more? Why or why not?”

Kim: I used to paint. I used to be a painter before I started studying sound art. I totally suck at painting. I totally suck. And I didn't enjoy the process of painting. It was aggravating for me and I thought, why should I torture myself? So I kind of gave that up. And then I got really excited with sound art and it was a new world for me, and conceptual art, which I became totally entranced and involved in, but I miss working with my hands. I couldn't just work with sound. I felt like something tangible was needed. And so I started with charcoal and I use graphic charts mostly. And I'm still a little bit afraid of color. I have added some color, but yes, I'm still a little bit scared. Maybe I'll take that step soon.

Uyeda: Ok let's make this the last question. It's about process and it's from an anonymous attendee. “How do you develop your words? Do you start with an idea fully formed or do you iterate and make lots of tweaks?”

Kim: Okay. What people see on the surface is my website or my social media. And it looks like everything's fully developed, but I have so much bad work that obviously is not online. What you see is maybe 10 or 20%, which is amazing. The other stuff I'm not uploading to social media. There's a huge process for my drawings. I often think of an idea. And I think of which format, which paper, what kind of graphic or drawing. So for example, for the national anthem, I had maybe four before this one, four drawings that I just ripped up and threw away. And these, this is a lot of large paper, but I was like, no, it didn't fit it. Wasn't what I wanted. Some drawings continue on and I do more and more and some are perfect. And that becomes my final product.

Uyeda: Okay. With that, I think we'll wrap up. Thank you so much, Christine, for joining us and for walking us through the show, it's such a pleasure to have you and to check in and say hi from Berlin.

Kim: Thanks so much. Thank you for organizing this event again and thank you Francine. Bye bye.